The composite pattern as explained by the Gang of Four is a design pattern which allows you to "compose objects into tree structures to represent part-whole hierarchies." If you want to have a better understanding of how your favorite frameworks work or learn to build your own view framework, this pattern is the place to start. JavaScript frameworks like React and Vue use the composite pattern to build user interfaces. Each view is represented as a component, and a component can be composed of multiple components. Using components is preferable because it is easier to develop and scale an application that uses multiple smaller objects instead of working with fewer monolithic objects.

What makes this pattern so powerful is that individual objects can be treated the same as composite objects because they share an interface. This means you can reuse objects without worrying about whether they will play nicely with others. While it may seem more obvious to use this pattern in the design of user interfaces or graphics, it is possible to use the composite pattern in any case where the objects in your application have a tree structure. To give you a different perspective, in this post you will be learning how to use the composite pattern by designing a game engine.

Overview of the Composite Pattern

The composite pattern consists of components, leaves, and composites. A component is an abstract class which can be used as either a leaf object or a composite object. It contains methods for managing child objects like add, remove and getChild and methods specific to all components. A leaf is a subclass of a component that has no child objects and defines behavior for an individual object. A composite is a subclass of a component that stores child components and defines the behavior for operating on objects that have children.

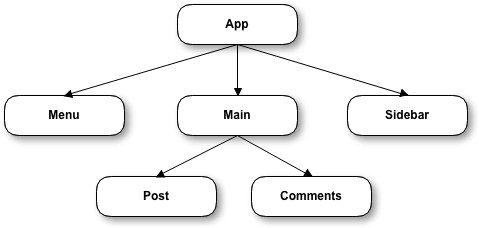

If you were designing a user interface for a blog application, you could partition the views into a menu component, sidebar component, and main component. The main component could be a composite made up of the post and comments. Each of these objects would share a draw or render method where you define the template. This is an example of a tree for the UI:

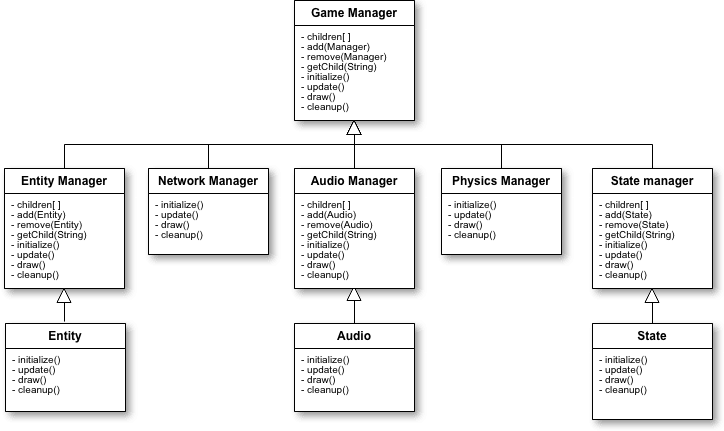

If you were building your own game engine, you could use the composite pattern to make the system more modular. A game engine may feature tools for managing entities, managing state, and managing audio among other things. Each of these managers could be modeled as a component. This is a diagram for the class hierarchy of a game engine:

Game Engine Implementation

For this example, we will implement a game engine that has an entity manager and a Physics manager. The engine is a composite that contains the entity manager and Physics manager components. The entity manager is also a composite and contains other entities as children. The first class we will create is the Component base class. Since these examples will only print to the console, I have chosen to use Node.js so you can execute the code from your command line and without needing a module loader. This is the Component.js class file:

class Component {

constructor(props) {

this.props = props;

}

update() {

console.log('default update');

}

add(child) {

this.props.children.push(child);

}

remove(child) {

this.props.children.splice(this.props.children.indexOf(child));

}

getChild(name) {

return this.props.children.find(function(child){

return child.props.name == name;

});

}

}

module.exports = Component;

The props parameter is an object literal that we will use to set the component's name and keep a list of all child component's for composite objects. The update method of this class will be overridden in each of our subclasses. In an actual game engine, you may also have an init, render, and cleanup methods but we will keep our code simple. Because the Engine class and EntityManager class are composites, their update method will be designed to loop through the list of child objects calling update on each one. Other component-specific behavior can also be defined in this method.

//Engine.js

const Component = require('./Component');

class Engine extends Component {

update() {

for (const child of this.props.children) {

child.update();

}

}

}

module.exports = Engine;

//EntityManager.js

const Component = require('./Component');

class EntityManager extends Component {

update() {

for (const child of this.props.children) {

child.update();

}

}

}

module.exports = EntityManager;

Because the PhysicsManager class and Entity class are simple components with no children, their update methods should define their behavior explicitly.

//PhysicsManager.js

const Component = require('./Component');

class PhysicsManager extends Component {

update() {

console.log(this.props.name + ' updated');

}

}

module.exports = PhysicsManager;

//Entity.js

const Component = require('./Component');

class Entity extends Component {

update() {

console.log(this.props.name + ' entity updated');

}

}

module.exports = Entity;

Now we will bring together everything and start our engine:

//index.js

const Engine = require('./Engine');

const EntityManager = require('./EntityManager');

const Entity = require('./Entity');

const PhysicsManager = require('./PhysicsManager');

const physicsManager = new PhysicsManager({name: 'PHYSICS_MANAGER'});

const playerEntity = new Entity({name: 'PLAYER'});

const nonPlayerEntity = new Entity({name: 'NON_PLAYER'});

const entityManager = new EntityManager({

name: 'ENTITY_MANAGER',

children: [playerEntity, nonPlayerEntity]

});

const engine = new Engine({

name: 'ENGINE',

children: [physicsManager, entityManager]

});

engine.update();

The output will be:

PHYSICS_MANAGER updated

PLAYER entity updated

NON_PLAYER entity updated

The call to update the engine would most likely be contained in the game loop so that at each frame or step engine.update() is invoked. Another thing to consider is how the objects were instantiated. All of the classes are included in our main file and instantiated one at a time. If you have many managers to include in the engine, you might consider iterating through the list of files to add them. This way anytime you add a new file, the object's children will automatically add the component.

Conclusion

The composite pattern organizes code in a tree-like hierarchy of objects. It reduces the complexity of a system by allowing you to work with small objects and build them up into larger ones. This is possible because there is no distinction to the client between a primitive object and a composite object. In our game engine example, the client doesn't have to know how each manager works to initialize it. They just need to know what the interface is (in this case the update method).

Although we used inheritance to create the components, it isn’t a requirement. Having a base class provides us with direction on how to use the other classes without having to dig around the code, and it serves as a template for creating other similar objects. Additionally, since the add, remove and getChild methods won’t be changing for the other components, it saves us from repeating ourselves in child classes by defining them only in the base class.

You might also change how properties are passed to the components. Instead of using this.props = props we could have explicitly stated all of the properties we expected the components to have. That would help to document how to use the class. Then in subclasses, we could add component specific properties. There are many ways you can alter the code to fit your needs. I encourage you to play with the examples and use the code in your own projects.

TABLE OF CONTENTS