It all started with a meme.

This one involved created an insult from everybody's favorite abusive television chef, Gordon Ramsay, by picking a value from three columns.

- First, you take your month of birth and match it up with an aggressive statement. So let's say you were born in November, your statement would be "Get a Grip!".

- Then take the first letter of your first name and do the same. If your name is Sam, then the next part would be "You Proud".

- And finally, take the first letter of your last name and find the associated value in the third column. If your last name is Quixote, the final part would be "Gremlin!"

Put together, our insult for Sam Quixote, born in November, would be "Get a Grip! You Proud Gremlin!".

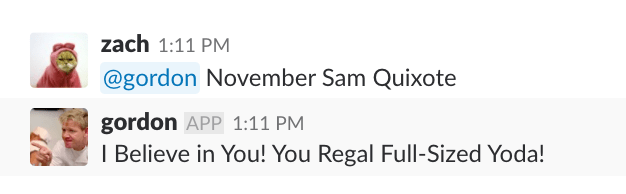

Immediately, I thought this might make for a bit of good fun as a slack bot. I've played around with the options here to make our friend Gordon dramatically more supportive instead of the unfortunate verbal tirades. Our friend Sam's message from Gordon is now this:

This article outlines that whole process and highlights some of the concurrency features of golang. If you're interested in a compelling alternative to the callbacks and promises of JS, read on!

Let's first setup a slack bot for your team:

- Go to https://your-slack-team.slack.com/apps/new

- Name your bot and add it to slack. I've called ours Gordon.

- In "Integration Settings", record the API Token.

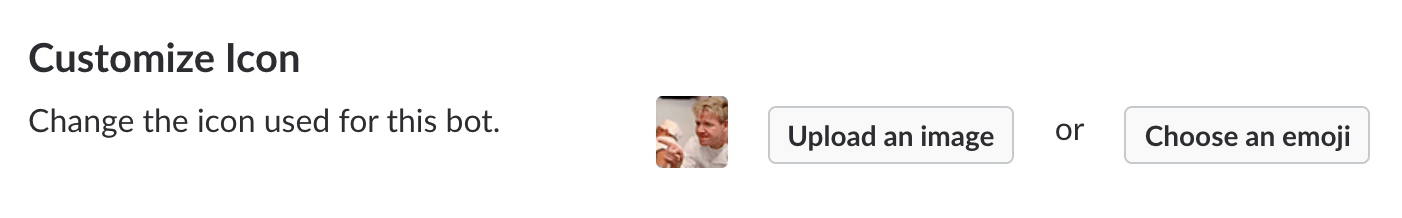

- Make a little profile image for adorable robotic Gordon:

Now we can get to the actual code!

We're going to use a great go client library for slack called... slack, so we'll install that:

go get github.com/nlopes/slack

This client library interacts with Slack's Real Time Message API (RTM) (https://api.slack.com/rtm). It's a very neat API that's WebSocket-based, so we'll receive events from slack's backend as soon as they occur. Let's start the library and make sure we can see events flowing.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"os"

"strings"

"github.com/nlopes/slack"

)

func main() {

api := slack.New("<API-TOKEN-SECRET-SAUCE")

logger := log.New(os.Stdout, "slack-bot: ", log.Lshortfile|log.LstdFlags)

slack.SetLogger(logger)

api.SetDebug(true)

rtm := api.NewRTM()

go rtm.ManageConnection()

for msg := range rtm.IncomingEvents {

fmt.Println("Event Received: %s\n", msg.Data)

}

}

The guts of this are what's called a goroutine in golang, which establishes and manages our WebSocket connection to Slack:

go rtm.ManageConnection()

This little gem will also handle reconnecting if your connection fails for some reason.

We can then receive events from the rtm object's IncomingEvents channel. For now, we're just going to print out the Type field of any events we're receiving.

for msg := range rtm.IncomingEvents {

fmt.Println("Event Received: ", msg.Type)

}

This is a great example of the simplicity of golang's concurrency primitives. Instead of something like a javascript callback, we set up a loop which will await all events on the channel. It's a very synchronous-looking piece of code, but it's actually describing two sequences executing separately. One is the Slack client library's internal WebSocket processing, which is placing events on the IncomingEvents channel. The other is our implementation's loop, which is awaiting those events and performing some action when they're received.

Channels, goroutines, and go's other concurrency primitives are based on ideas from CSP research (Communicating Sequential Processes). A core tenet of go is this:

Do not communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.

So go attempts to hide more complex ideas like semaphores and memory fences, leaving you free to focus on events flowing through channels to loops receiving messages.

In contrast, Javascript doesn't execute across multiple threads, so it's not even possible to share memory. There are no semaphores in happy go lucky JS-land because everything executes in an essentially atomic manner. You can run multiple node processes in a cluster sort of system, but getting them to interact and properly handle IPC can be challenging. Go, on the other hand, is built for this. It provides users with a rich set of tools to manage applications that maximally use available resources.

Back to our favorite chef-bot!

Running this should now briefly spam your terminal. Note that I've removed sensitive information and replaced it with REDACTED.

go run main.go

Event Received: connecting

slack-bot: 2018/02/12 16:53:45 slack.go:123: Starting RTM

slack-bot: 2018/02/12 16:53:45 <autogenerated>:1: parseResponseBody: {REDACTED}

slack-bot: 2018/02/12 16:53:45 slack.go:130: Using URL: wss://REDACTED

slack-bot: 2018/02/12 16:53:45 slack.go:123: Dialing to websocket on url wss://REDACTED

slack-bot: 2018/02/12 16:53:46 slack.go:123: RTM connection succeeded on try 1

Event Received: connected

slack-bot: 2018/02/12 16:53:46 slack.go:130: Incoming Event: {"type": "hello"}

Event Received: hello

Alrighty! So we've got a realtime connection to Slack's bot API and we can start doing interesting things.

We'll now check for the type of message, and post a very ragey message from our Gordon Ramsay bot if somebody is tagging the bot in a message. Inside our loop, we'll add the following snippet:

switch ev := msg.Data.(type) {

case *slack.MessageEvent:

botTagString := fmt.Sprintf("<@%s>", rtm.GetInfo().User.ID)

if !strings.Contains(ev.Msg.Text, botTagString) {

continue

}

rtm.SendMessage(rtm.NewOutgoingMessage("IT'S BURNTTTT!", ev.Channel))

default:

}

What's this doing? We check all incoming message events for when our bot is tagged with "@", and then we send a message to the same channel where that message came from. The empty default case there will allow our channel to receive the message and ignore all other event types sent on the channel without blocking.

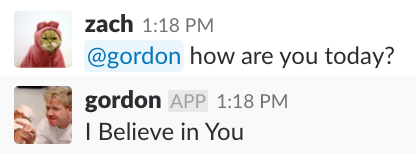

Running this results in something like this:

Now, let's do something a bit fancier and match what's in our meme. We need to watch for messages of the form:

"@gordon

So we'll take our message and split it into its component parts, sending a message if the user doesn't send a message with enough parts to it.

messageParts := strings.Split(message, " ")

if len(messageParts) != 3 {

rtm.SendMessage(rtm.NewOutgoingMessage("I Believe in You", ev.Channel))

}

Then we have a few very simple lookup tables (simplified for brevity) that we can search through to create a personalized insult, courtesy of our abusive friend Gordon Ramsay.

var sentenceStartMap = map[string]string{

"january": "Way to Go!",

"december": "Magnificent Effort!",

}

var sentenceAdjectiveMap = map[string]string{

"a": "You Rainbow-Infused",

"b": "You Molten",

"c": "You Inspiring",

"z": "You Clever",

}

var sentenceNounMap = map[string]string{

"a": "Echidna!",

"b": "Musk Ox!",

"c": "Land Mermaid",

"y": "Apocalyptic gladiator",

"z": "Genius",

}

sentenceParts := []string{}

sentenceStart, ok := sentenceStartMap[strings.ToLower(month)]

if !ok {

rtm.SendMessage(rtm.NewOutgoingMessage("I Believe in You", ev.Channel))

}

sentenceParts = append(sentenceParts, sentenceStart)

firstNameLetter := strings.ToLower(string(firstName[0]))

sentenceAdjective, ok := sentenceAdjectiveMap[firstNameLetter]

if !ok {

rtm.SendMessage(rtm.NewOutgoingMessage("I Believe in You", ev.Channel))

}

sentenceParts = append(sentenceParts, sentenceAdjective)

lastNameLetter := strings.ToLower(string(lastName[0]))

sentenceNoun, ok := sentenceNounMap[lastNameLetter]

if !ok {

rtm.SendMessage(rtm.NewOutgoingMessage("I Believe in You", ev.Channel))

}

sentenceParts = append(sentenceParts, sentenceNoun)

message := strings.Join(sentenceParts, " ")

And finally we can send our message:

rtm.SendMessage(rtm.NewOutgoingMessage(message, ev.Channel))

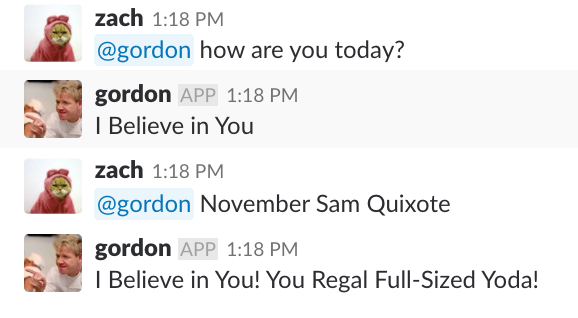

Running this:

Well done Gordon!

You can find a cleaned up version of this code at https://github.com/zachgoldstein/gordonBot. There's a whole slew of things to do before this would be ready for production, but a few of them are in place in this code. I've added a few tests for the guts of this, and instead of hard-coding your API-key you can pass it in via a command line flag. If you'd like to see how what that looks like, definitely check it out.